This is something that’s brought up constantly when people talk about sustainability, and it’s often a marker of how much they pay attention to it: the interchangeability or not of the words compostable and biodegradable. So pitting them against each other, compostable vs. biodegradable: What do they mean, which one should you use, and why does it matter?

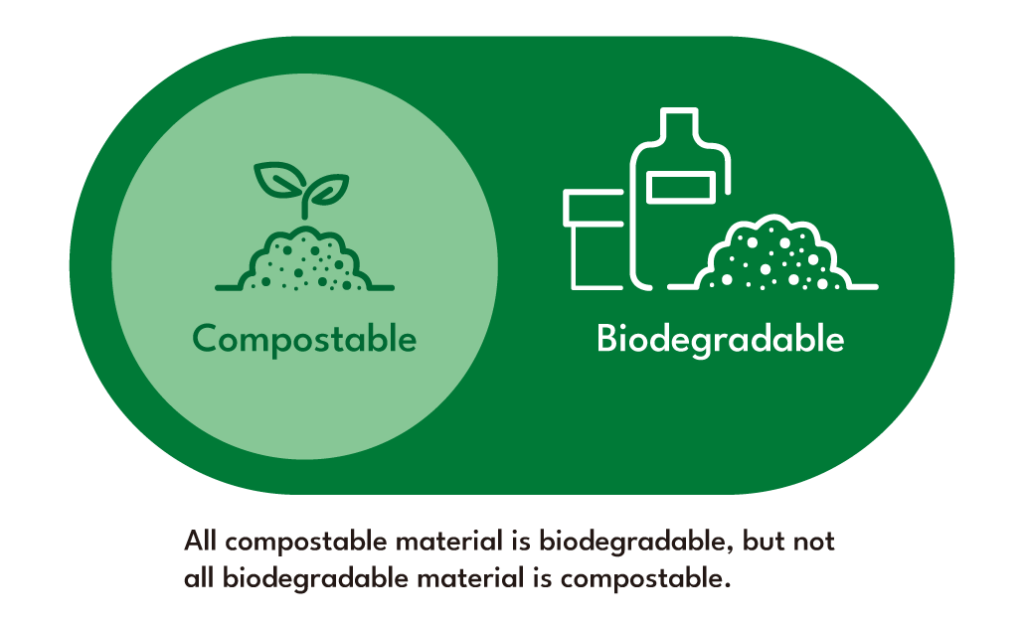

Sustainability professionals are careful in how they use these words because everything is biodegradable, but not everything is compostable, and when it comes to communicating product disposal, brands often use them willy-nilly. So first, here are their definitions from the Oxford English Dictionary:

Biodegradable: Able to be broken down and decomposed by the action of living organisms (esp. bacteria), or their metabolic or biochemical processes.

Compostable: Of organic matter, esp. kitchen and garden waste: capable of being turned into compost.

Those definitions may seem similar on the surface, but how they’re used in corporate lingo and customer facing marketing has far-reaching effects.

Biodegradable Breakdown

So looking more closely, brands often use biodegradable as a catch-all for anything they want to label “green.” But basically, everything is biodegradable. Or most everything. Rocks aren’t, really. Rock ‘n’ roll, I don’t know. But everything else is biodegradable—even steel, which is broken down by microbacteria. (Steel is metal, so rock ‘n’ roll is probably biodegradable.)

Plastic, tires, treated wood—everything is biodegradable. It will all break down, eventually. So how long will each of those take? In the case of plastics, it varies. A plastic bag can take 20 years, a plastic ring 6-pack can take 400 years, and a disposable diaper can take 500 years. These are all estimates, obviously—plastic has only been in wide circulation since the 1950s.

As for tires, those take 50-80 years (they’re made primarily from synthetic materials and a little bit of vulcanized rubber these days). Treated wood also lasts around 50 years before it finally starts rotting—although it can start showing signs of rot in as little as 10 years for items like plywood. Rot is a form of biodegradation as bacteria, and fungi are responsible for the breakdown of the materials.

Based on those examples, you can see there’s an incredibly wide range of how long things can last if left in the environment. And they’ve all been called biodegradable at some point.

Compostable Breakdown

Now, looking at the word compostable, it seems similar to biodegradable. Made from organic matter, capable of being turned into compost. So let’s define compost.

Compost: A mixture of various ingredients for fertilizing or enriching land, a prepared manure or mold.

Basically compostable means that something can be turned into nutrients to help boost soil health. But again, what’s the difference between biodegradable and compostable?

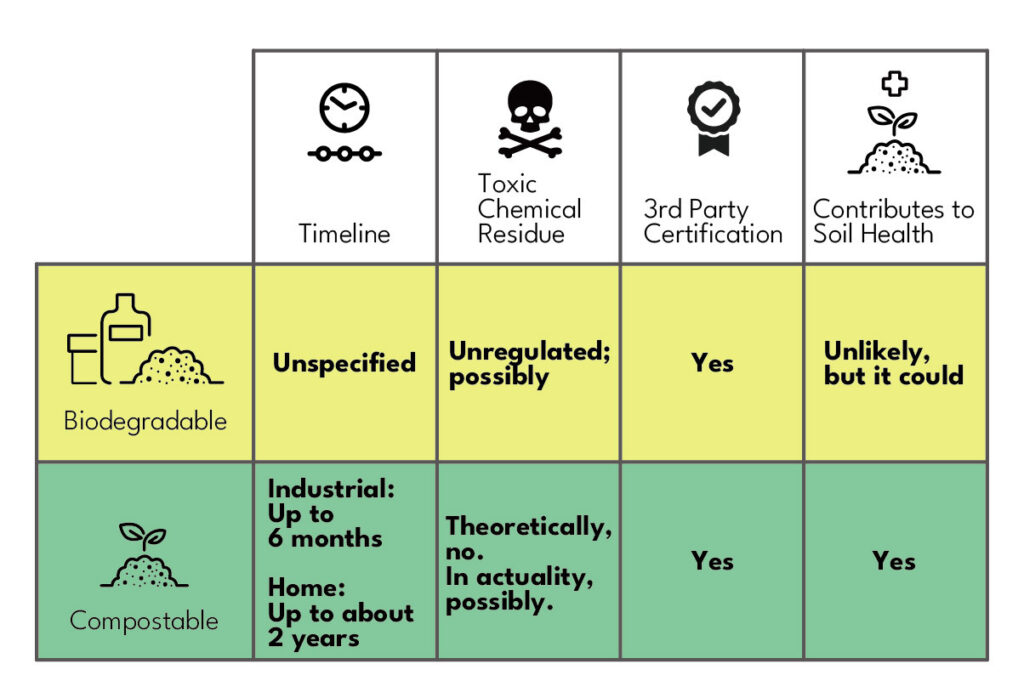

There’s a few things. Biodegradable doesn’t have a timeframe associated with it. And it really just refers to how something breaks down, not what it turns into. To be compostable, something has to be able to be turned into compost, and compost boosts soil health. That means there can’t be any toxic chemicals in the compost that could otherwise poison plants. Whereas anything that breaks down by biodegradation may have toxic chemicals in it.

There’s a few things. Biodegradable doesn’t have a timeframe associated with it. And it really just refers to how something breaks down, not what it turns into. To be compostable, something has to be able to be turned into compost, and compost boosts soil health. That means there shouldn’t be any toxic chemicals in the compost that could otherwise poison plants. Whereas anything that breaks down by biodegradation may have toxic chemicals in it. (However, as an example of toxic chemicals getting into compostable materials, with recent reports that PFAS has been found in recycled paper content, “shouldn’t be” and “won’t be” are two different things.)

Ok, so for something to be compostable, it must be able to be broken down in a reasonable timeframe—more on that in a moment—and it shouldn’t be toxic. (There’s also a difference between toxic and toxin, which are often used interchangeably. Toxics refers to human-made products, whereas toxins refer to natural, biological products. Think PFAS vs. a jellyfish.)

So there are two types of composting: industrial and home.

Industrial Composting

For something to be labeled industrial compostable, it needs to be able to decompose in an industrial composting facility. There are two certifications for plastics for this in the US: ASTM D6400, which is for plastic products such as packaging, and ASTM D6868, which is for plastic polymer coatings and additives on paper and other substrates. In the EU, the TUV certification for compostable packaging is EN 13432.

The following differentiates industrial composting from its home counterpart:

- Maintains temperatures between 50°C and 70°C

- Moisture levels are stabilized

- Is turned over consistently

- Must decompose and disintegrate between 3-6 months (a tree limb couldn’t be certified industrially compostable for this reason)

Home Composting

On the other hand, a home composting pile reaches temperatures between 32 and 60°C. And the time required for items to decompose can be up to two years, depending on fluctuations in temperature, how often a pile is turned over, and moisture levels. For this reason, some products are certified for industrial composting but not for home composting—they won’t break down unless under ideal conditions.

However, that’s not the only reason: There is actually no home compostable certification in the US currently. ASTM is working on one, but otherwise the notion of home compostability amongst new packaging biomaterials in the US has basically been companies using time-lapse video showing their products decaying in the ground.

There’s also nothing wrong with this, at the moment. If a company knows its products are compostable based on the manufacturing process and inputs, and is actively going through the process of certification, or has gone through the process but wants to show that home composting is also an option, then this type of promotion is generally fine. Could this be used for greenwashing? Oh, absolutely. But so far, the only companies making videos like this are ones who are confident in their products. Time will tell.

Now, in Europe, there are three home compostable certifications: TUV Austria has a OK compost HOME certification, France has NF T 51800, and the Europe-wide certification prEN 17427. And in Australia there is the AS 5810. All of these certifications cover either packaging specifically or compostable plastics generally.

Compostable vs. Biodegradable: The Showdown

We’ve seen the breakdown of each word, and the certifications required for compostability, but there’s one more factor that really shows the difference. Whether it’s industrial or home, there are four tests that determine the compostability of an item for certification:

- Biodegradation

- Disintegration

- Ecotoxicity (no negative effect on plants)

- Heavy metals content

An item needs to pass all four of these tests before it can be called compostable. And most products labeled biodegradable in the last 10 or 15 years probably couldn’t pass more than two of these. (Cleaning detergents used to be heavily marketed with biodegradable language.)

So why this breakdown? Because many brands and companies are still using biodegradable to their detriment, as some states, including California, Maryland, Minnesota, and Washington have banned the use of the word in marketing materials.

In the largest market in the US, a brand or company will be fined for using biodegradable in marketing. Which is why compostable is the right word to use when talking about something disintegrating toxic-free into soil. But to genuinely say that—and again, be greenwash-free—you need one of the certifications mentioned above.

But it should also be mentioned that composting isn’t always the best option. Paper, for instance, can usually be recycled. Going this route instead of composting would decrease the amount of virgin pulp needed for new paper. Reusing packaging is another option that would be more impactful than simply tossing something into the compost. But the fact is, even if extreme care is taken, not every item will be disposed of properly—wind happens. So using materials that have minimal effect on the environment—such as those that can be composted—is the more sustainable route.

Anyway, since this type of language—biodegradable, compostable—is often printed on packaging, it’s good to have a design house who knows the difference while they’re making packaging. So if you want packaging that’s greenwash-free, Zenpack can help.

If you want to know more about Zenpack’s services

Let our packaging consultants help you turn your idea into reality.