Man alive, everyone’s talking about packaging inks these days. Soy-based this, recyclable that. Where did it come from, and does it matter? Is it all just greenwashing to make companies feel better about printing on plastic? Why is there so much talk about something that’s so thin that it’s almost imperceptible to the touch?

Well, like most things regarding sustainability and our modern society, it comes down to chemicals. Inks are, you know, rather opaque. So let’s figure out what they are, why they matter, and how you can communicate their uses.

Recycling Inks

The definition of recycling is to “create (waste) into reusable material.” This is important to remember here.

When paper is recycled, the first stage is de-inking. There are four available processes for this: floating it in water and agents and shooting it with air bubbles, using bleach, using enzymes, or washing. The first process is the most common.

After shooting it with air bubbles, a froth is created on top—the ink is mixed into that—and it’s collected before the pulp moves onto the next step.

That froth is then discarded. It’s not turned into new ink or any new material. Therefore, ink is not recycled. They don’t hinder recycling, they don’t contaminate the pulp, but they are not recycled themselves.

So when that froth is disposed of, where does it go? This is one reason people are paying so much attention to inks these days. The waste has to go somewhere, and not all recycling plants in all countries are the same—after all, it’s a heck of a lot cheaper to dump it in a river than pay for water treatments, just ask UK water companies. And even though the recycling plant by your house might do things that are more in line with nature, you’re not just making products and packaging for your 5-mile radius.

So there you go. Ink doesn’t stop recycling. But it isn’t recycled. So if you ever see a company claim its inks are recyclable, it’s probably greenwashing.

Types of Packaging Ink

There are essentially four different types of ink depending on what type of printing method you’re using: oil-based (fossil, soy/vegetable), water-based, solvent-based, and UV. And then there’s algae, which is slowly scaling and only available in black at the moment, but we’ll talk about that later.

Let’s lay them out here, make it easier on the eye:

- Oil-based

- Water-based

- Solvent-based

- UV

- Algae and other biobased inks

Combine those main four with innumerable variations and the fact that there’s countless companies producing inks (Ink World Magazine lists the top 31 international companies by sales, with a cut-off of $48 million), and you can understand how things get complicated quickly.

Now, every ink contains four basic components. These are: solvent, pigment or dye, binder, and additive(s). Additionally, there can be resins or varnishes.

There are also different inks, mixtures, and chemicals for different substrates. If you’re printing on paper, coated paper, plastic, etc.—each one requires a different type of ink.

Leo Chao, Co-founder and Creative Director at Zenpack, explains the reason behind this. “Ink needs to adhere to your paper. It does not magically adhere to it. Traditionally, a color liquid absorbed into a fibrous surface and sort of got into it. Modern technology changed that because of the coating [on the paper]. Whatever this ink is made from, it’s not absorbed into the paper—it’s actually sitting on top, drying. Now, what is binding that? A water-based ink is not gonna stick to it. It’s not magical, you know, with any adhesiveness to it.”

As Chao says, ink needs a binder, something to make it stick to a surface. And this is how oils have been used for a long time, first fossil fuels, and now soy.

Oil-based Inks

These are the most common types of ink used in packaging, and are used on most everything except rigid plastic. This is also what most people are talking about these days with regards to inks. Fossil fuels or soy? Plastic or plants? And while it’s good we’re having the conversation, the origins of this conversation are questionable, according to Chao.

Case in point: Most conventional ink uses soy oil, and all soy ink uses some fossil fuels. In fact, to be considered soy ink, soy oil only has to be the predominant vegetable oil by weight. For black newspaper ink, this means 40% soybean oil. For stencil duplicator ink, only 6%. (Other vegetable oils used in inks include linseed and corn.)

So how does 6% soybean oil qualify for soy ink? “I think, personally, it started with a bit of greenwashing,” said Chao.

When the gas crisis enveloped the latter part of the 1970s, and there was no internet for people to get their news, newspapers started experimenting with soy oil in ink to lower costs. While nothing really came of it at first, soy oil was finally marketed for sale in 1987. (Some of the fossil fuels are replaced with soy oil.)

Initially soybean oil was more expensive, but the new inks made it easier to maintain machines and keep them clean. And with no visual difference between fossil fuels and soybean oil, by 1991 a third of the colored news ink market was held by soy ink. Today, soy inks are actually cheaper than fossil based inks in many situations.

“You know, the first time we were asked by a client, they said, ‘Hey, have you seen this? They [another company] say they print with soy ink.’ And at the time I wasn’t that concerned about it. It was like, ‘Oh, great. Yeah, that’s our supplier too.’

“So we asked, and our supplier said for the past two years all our printing had been with soy ink, ‘We just didn’t tell you about it.’ It’s such a standard thing now.”

If it’s so common, and a supplier driven aspect, as Chao put it, why are some brands promoting it so heavily, while other brands are barely saying a peep?

“I think it was someone saying, ‘Can we say we’re using soy ink and then it’ll sound better and we can charge people more?’ I think that’s how it became a thing. ‘Oh, I saw this—Starbucks printed with soy ink. Why don’t we do it?’ And then they’re asking the supplier, and the supplier says ‘Of course, we were using that 10 years ago. Sure, we can put it there.’ I honestly think that’s what happened.

“I’m still proud of it. Even though this is a supplier side initiative, it’s still a good move. No one forced them to do it… But to give it a name, that’s a marketing thing.”

So if soy inks are a marketing thing, why does it matter if we use them? For one, using anything renewable is a win. Whenever we can reduce drilling and fracking of oil and gas, there’s a chance to reduce GHG emissions. Obviously farming soybeans still uses diesel tractors, but does that still equate to fewer emissions overall? (This is rhetorical, as individual oil and gas well emissions are not exactly tracked diligently.)

Soy ink also uses less VOCs (volatile organic compounds), which are not great for human health. Additionally, if we’re using less fossil fuels in ink, then that froth from paper recycling should contain fewer toxic chemicals overall. And again, that froth has to go somewhere.

So is that about it for inks? Well, nowhere above did I mention what’s in them. That’s because, again, it depends. With so many companies and formulations out there, no two inks are exactly alike in chemicals, additives, and all that junk that you wouldn’t want to pour on your breakfast cereal.

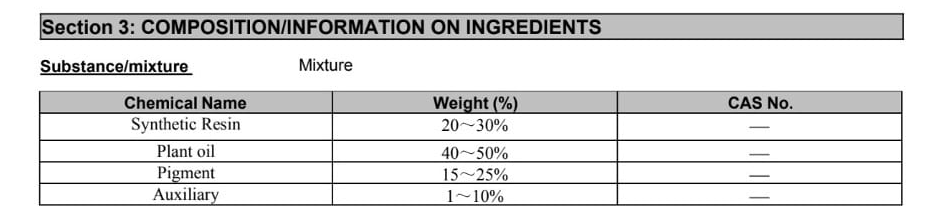

Chao advises to ask for the MSDS (Material Safety Data Sheet) from your suppliers. That will give you detailed information on exactly what goes into the inks you’re using. Below is the ingredients list from an MSDS that Zenpack received while looking for a plastic free ink. Some are more detailed than others, but this gives an idea of what one looks like.

Water-based Inks

Water-based inks are the oldest inks. They were mixed with charcoal and other nature-based dyes thousands of years ago, and combined with gums and tree saps that acted as binders. Today, water-based inks are pretty much like oil-based inks, in that they have pigments, binders, and other additives. They do use less solvents, and are supposedly easier to recycle—although that just means separating them from paper.

Some companies claim that their water-based inks are free from plasticizers, but unless there’s an MSDS to accompany those statements, it’s important to remember that a plasticizer is just one of many possible synthetic components to inks, so they still are likely not plastic free.

These inks are used primarily on flexo print, which is basically a rubber stamp on a big drum. Rather than drying on top of a surface, like oil-based inks, water-based inks are absorbed into a substrate.

They work best on corrugated cardboard and uncoated paper. Since the ink is absorbed into a material, the resolution is not as high compared to oil-based inks, but Chao said that you can still achieve a very high-quality print—it’ll just look a little different.

So should you ask for water-based inks? “If someone asks me, ‘What’s the best ink you can print with today?’ I would say anything water-based is probably better. But you’re sacrificing quite a bit in terms of print quantity, quality, resolution, and how small your texts can be. So that’s that.”

Solvent-based Inks

There’s not really too much to say about solvents, except that they’re primarily alcohol-based and typically used for flexible plastic. They use the same types of pigments, additives, and resins as the other inks above, and only their base differs so as to adhere to different substrates.

UV Inks

UV inks are the only type that can print on rigid plastic. Unlike oil-based inks, UV ink does not contain soybean oil and is completely fossil fuel-derived. There are some proponents of UV inks because there’s less water and energy used to print, but as Chao says, they’re ignoring other aspects.

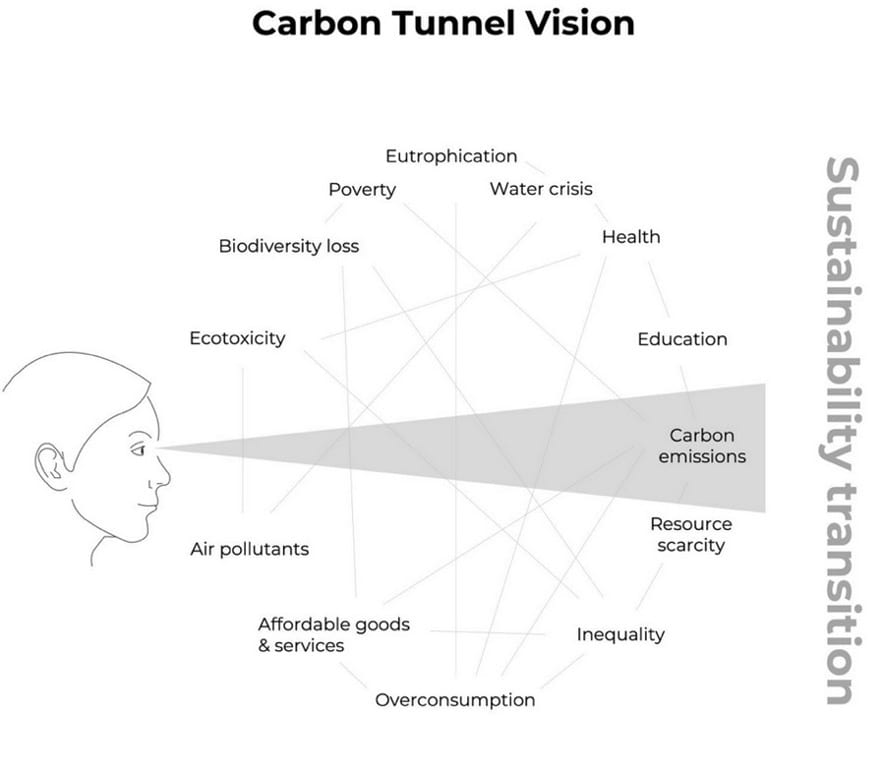

This feels like a good time to point out the term “carbon tunnel vision.” It means exactly what it sounds like. People get so focused on carbon emissions, such as less energy required to print UV inks, that they ignore all the other factors contributing to climate change.

When waste and pollution related to UV inks are ignored, that’s a clear cut case of carbon tunnel vision. While Chao doesn’t completely write off UV inks—he says Zenpack uses them on uncoated surfaces on occasion, when they need a high quality print for a client—he does question the loud assertions of “these are best.”

He says on one hand, with UV inks, you don’t need to coat or laminate a surface, because the ink essentially does that when it’s cured under UV lights. But on the other hand, it is still a thick, petrochemical solution that needs to be separated during recycling or, if the packaging finds its way into the natural environment, will be left to degrade and pollute its synthetic chemicals into soil and air.

Algae & Other Bio Inks

The biomaterial company, Living Ink, is producing its algae ink for use in packaging and printing. The ink is only available in black, and the company says it’s similar to traditional inks (read: synthetic components involved) except that its pigment is made from algae, which is renewable and biobased. The company claims it’s a net negative company because of the carbon algae pulls from the air while growing.

The black algae pigment replaces carbon black—a heavy oil product—and from which most black ink is derived. It’s claimed that this is the only ink that uses pigment from a renewable resource.

Another company working on pigment is Nature Coatings, which makes BioBlack TX. This is another replacement for carbon black and is made from wood waste. The company is looking to use BioBlack TX for many applications that would normally use carbon black, including packaging and printing.

One more company doing something interesting with unconventional inks is Graviky, with their invention Air-Ink. The Indian company pulls carbon emissions and particulate matter directly from the air and turns them into a replacement for carbon black. They then use this air pollution to create a water-based, flexo print ink, among other things (the company has also partnered with Pangaia to get into textile printing).

Dyes & Pigments

As mentioned above, almost all pigments used in commercial inks are made from petrochemicals.

As for dyes, they aren’t used as much for packaging inks. While both are colorants, dyes are soluble and pigments are not. Instead, pigments are suspended in a binder (If you remember towards the top, all inks have a binder in them).

There is a lot of work going on to make natural dyes, but unfortunately, at least for the packaging world, all that work is focused on textiles and fashion currently—or at least the work that’s emerged from the lab.

Concerns for Food Packaging

Mineral oils are often used for solvents and resins. More attention is being focused on this recently as mineral oils can rub off from food packaging and directly contaminate products. Beyond food, this can still happen with any type of packaging if someone touches their mouth after handling the packaging.

France and the EU have recently banned mineral oils in food packaging inks, but they’re still allowed in many countries around the world including the US. MOAH (mineral oil aromatic hydrocarbons) can apparently cause cancerous tumors, and MOSH (saturated mineral oils) have been shown to contaminate food eaten by consumers.

With the bans in place, there are now mineral free inks available on the market, but that still leaves you with a choice now. Use these slightly more expensive inks for your packaging because it’s kind of the right thing to do—not contaminating your customers’ food and all—or continue to use these inks in any place where there isn’t a ban because, you know, it’s cheaper.

People Who Know More-ish About Packaging Inks

Man alive, there’s a lot to know about inks. And this really just scratches the surface. If you want to know more, ask your supplier for an MSDS. It’s the most comprehensive way to find out what’s in your inks.

And if you need a supplier who will get you an MSDS, talk to Zenpack. We’re all about transparency—it’s better than being opaque.

If you want to know more about Zenpack’s services

Let our packaging consultants help you turn your idea into reality.